Meet the Artist: Chelsea Locklear

Learn about the story behind the mural NC State alumna created for Poole College to celebrate Native American Heritage Month.

By Lea Hart

November is a month of celebration of the beauty of Indigenous cultures. Poole College of Management takes this month to recognize the tremendous positive significance Native people have made in this country, but also to remember the horror of past and current mistreatment of Native communities who continue to fight for recognition, equality and peace.

Q&A with Chelsea Locklear

Tell us about your cultural background as it relates to this project?

I am a member of the Lumbee tribe of North Carolina. I am from Pembroke, which is the home of Lumbee people. I grew up in my tribal community and have close ties to that community. My family still lives there. For a lot of people like myself who grow up in a tribal community, it’s a bit of a cultural shock when you leave your community. For me, that first experience was NC State – moving into the dorms all those years ago. My town was 90 percent Native American. Most of my friends were as well. We have cultural ties to things we celebrate and we have our own traditions. For example, during the week of July 4th we have a weeklong celebration called Lumbee Homecoming. It’s a time to celebrate our people, who we are, and reconnect with each other.

Why is your cultural background important to you, personally?

For me, it’s really important to know where home is and to have those ties, especially to family. Family is at the center of the Lumbee culture. We’re a matriarchal people. That meant gathering with family at your grandmother’s house. You can see that influence outside of our tribe, throughout the South. Indigenous culture really is weaved into Southern culture, but really, it’s the reverse. A lot of people take for granted that many of your food ways and your cultural ways actually come from indigenous people.

You’re an NC State alumni. What was most meaningful to you about your time at NC State?

I did a campus tour and just fell in love with the environment. Pembroke was really small and Raleigh felt like the big city. I was just excited to move somewhere new and be away from home; to go out and discover new things. I was an international studies major and I loved the program. I really enjoyed learning about cultures different from my own, and how they still share a lot of similarities. The more people are different, the more they’re actually alike.

While I was there, I was involved with the Native American Student Association (NASA), as well as the American Indian Science & Engineering Society. Even though I wasn’t a science or engineering major, I was looking for any connection to stay involved with native people. During those four years, I learned a lot about how to represent who I am and who my people are, especially on a predominantly white campus.

How did you become involved in this artwork project?

My husband and I run a business on the side called Scuffletown Suppliers. We make shirts, socks and other apparel and gift ideas. It’s all geared toward the Lumbee and indigenous people. Before the pandemic, NASA asked if I would help design a t-shirt for Indigenous People’s Day. That design later landed in the hands of Tayah Butler (Director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion at Poole College). She reached out and asked if they could turn it into a banner. The design featured the state of North Carolina and the theme was, “Our Fire Still Burns.” She reached out this year to see if I could work on some additional pieces.

Tell us about the three pieces you’ve designed this year. What does each represent?

The first, with the wolf design, I call my “Indigi-Wolf.” I really wanted to incorporate the wolf into one of my designs because I love the Wolfpack. I included a couple of “easter eggs” (the term means a hidden reference stashed in a work of art). You can find traditional woodland tattoos that men and women would have on their bodies.

From the wolf’s mouth, you can see Eastern woodland florals and food, such as corn and berries. Most don’t think of the fact that this is indigenous food. Indigenous people were really great at cultivating their seeds and have served as keepers of these seeds. You’ll also see the bottom of a pinecone. This is something that’s represented in Lumbee culture and in traditional Lumbee regalia.

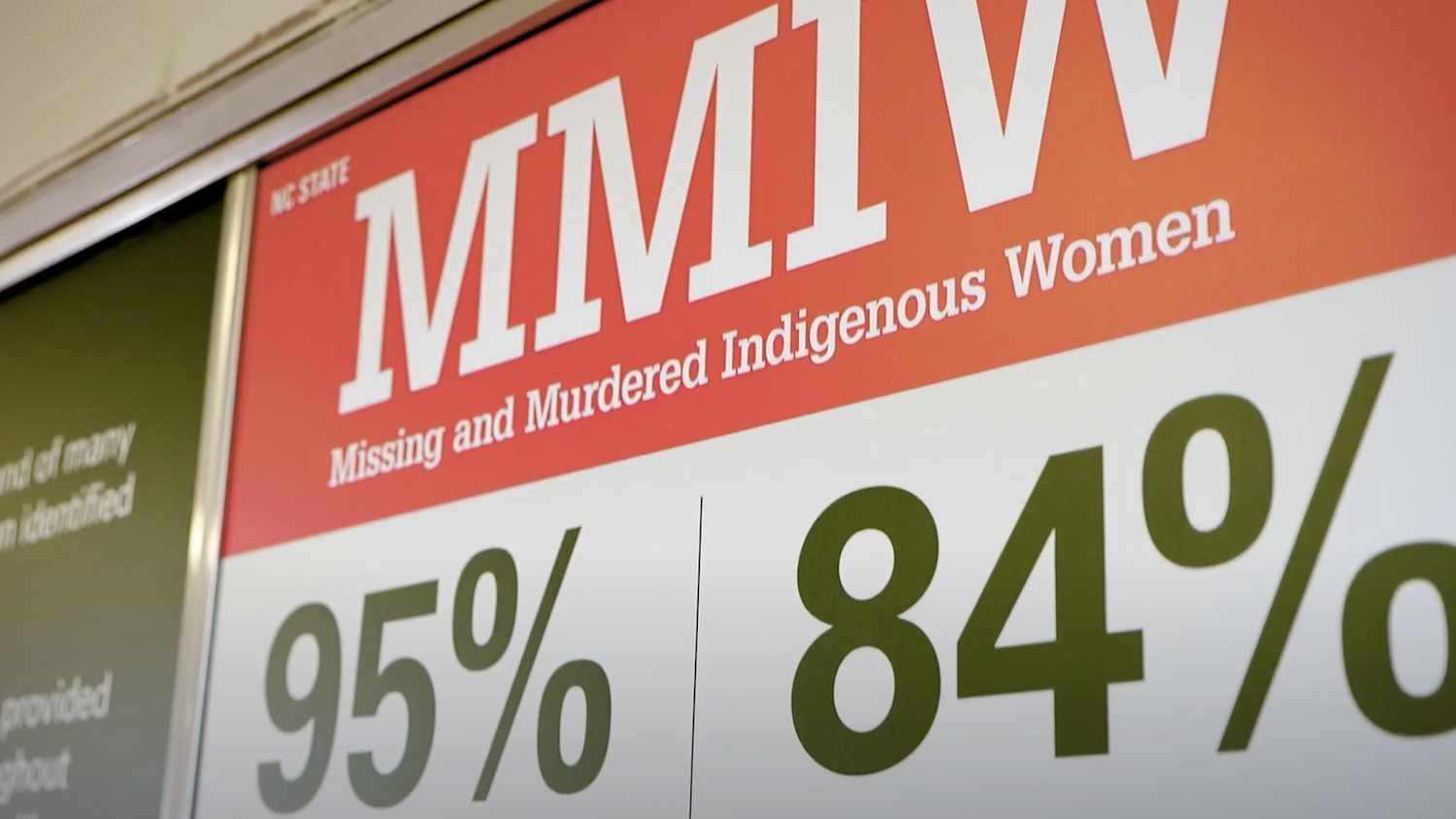

The second is an MMIW piece (MMIW stands for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, a human-rights crisis disproportionately affecting Indigenous peoples in Canada and the United States). Often a red hand is used to depict this movement, but I wanted to avoid that. It can be triggering to people. Instead, I thought about what happens when we lose our women and girls. Women are the life-givers of our community. The Eastern Woodland florals depict the loss of her beauty. The feather depicts the loss of our culture. The cob of corn depicts what she teaches us about our food ways. And the baby in the cradle signifies that, when a woman is murdered, we lose our next seven generations.

The canoe signifies that as our women leave us, I hope it’s on a beautiful canoe journey to our creator, even if they did not leave us in a peaceful way. The artwork goes in four directions – the four directions of our creator. I was thinking about how powerful our women are, tied to every element of Earth. The center looks like an hourglass, thinking about how we lose time with those that are taken from us. I really wanted non-indigenous people to think about the piece and think about how it would resonate with them. Even if you weren’t indigenous, you’d think what your family lost when you lost your grandmother or mother.

The last piece looks like a postcard. It’s a greeting from indigenous North Carolina. It has its own symbolism, including the pinecone patchwork, and the sunflower that I use heavily throughout my artwork. It lists all of the indigenous communities that still exist in the state today or existed in the past.

Where did you look for inspiration when thinking about what you wanted to create for these works?

For the “Indigi-wolf,” NC State was always my inspiration for that. I wanted something that would resonate with students. The MMIW piece was based on a lot of experiences I’ve had lately. I host the Red Justice podcast, talking about missing indigenous people – women and men – in the U.S. and Canada. I spent a lot of time over the last year or so, interviewing their families. My co-host and I talk with them about what our men and women take with them when they’re abruptly taken from us or abruptly go missing. It’s a very heavy theme. And again, I wanted something that would resonate with non-indigenous people.

What do you hope they will mean to the NC State & Poole College community of students, faculty and staff?

I hope that indigenous students love that they see representation of themselves. When I was a student, I did not see a lot of indigenous artwork hanging around campus. I hope I did them proud. For the MMIW piece especially, there’s also a poster of stats along with it. People don’t realize that 95 percent of indigenous cases do not get media attention. Many don’t realize that our women and children are going missing and getting murdered at alarming rates.

This is about bringing awareness to such a huge issue in our communities that most people don’t know about. I really hope that it drives people to learn that the issue of missing and murdered indigenous people is not a new issue. It’s really been going on since colonization. Columbus would kidnap and rape indigenous girls as young as nine and ten years old. Indigenous people have been sex-trafficked for hundreds of years. It’s an issue we’re still fighting today.

How do you think these pieces help embrace and support diversity and inclusion on campus?

As I mentioned, when I was a student, I don’t remember seeing a lot of artwork that was up in different buildings that was representative of native students. I hope native students will see themselves there and see themselves represented. Thinking about not just indigenous people, but also Latinx and other groups, decolonizing spaces means including other cultures and making sure they’re represented. I think Tayah has done an amazing job with this.

- Categories: