Dogs or Ventilators: Where is the Real Shortage?

Robert Handfield, executive director of Supply Chain Resource Cooperative and Bank of America University distinguished professor of operations and supply chain management at Poole College, explains the impact of COVID-19 on the global supply chain on everything from hot dogs to pharmaceuticals.

The current pandemic has created a panic among the general population, and in some cases, it is misplaced. For example, grocery stores have seen massive stock-outs of common items that people are beginning to hoard as a result of the coronavirus. Sales of toilet paper and paper towels have shot up by 70%, rice sales by 50%, beans by 50%, canned meat by 40%, and sales of peanut butter, bottled water, and pasta by 30%.

Hot dogs, for some reason, have jumped in sales by 300%!

In reality, Americans are unlikely to use any more of these products than they have in the past, and manufacturers are unlikely to have shortages. The only thing that is limited is shelf space in stores, but in reality, distributors have warehouses full of these products – and are not going to run out any time soon.

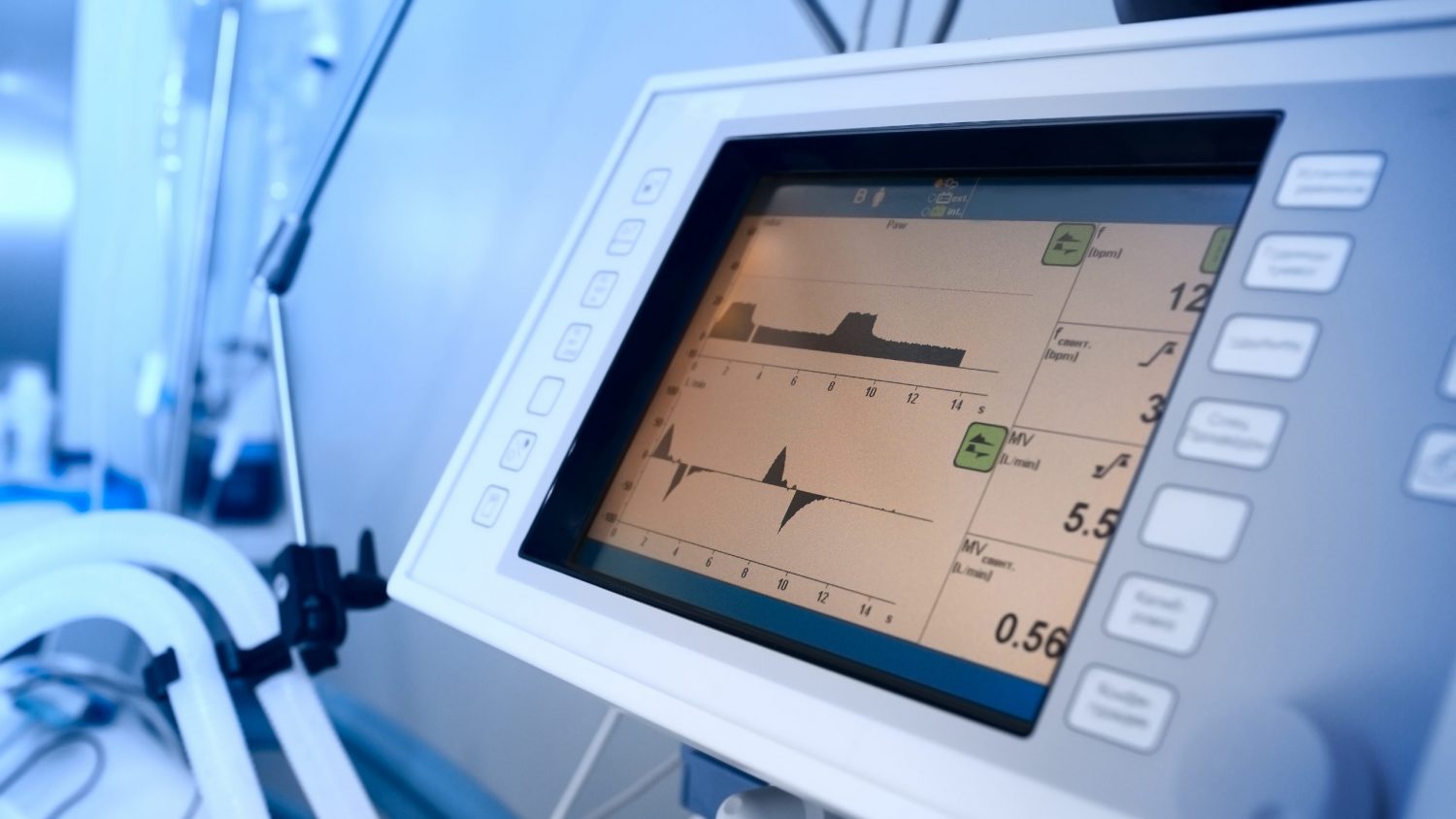

From a supply chain perspective, a much greater concern is the shortage of ventilators. In New York alone, there are an estimated 7,250 ventilators, and projections are that they will need more than 18,600. Some of the shortage can be addressed by canceling elective procedures and using anesthesia equipment in lieu of ventilators. A Time article suggests that there are about 62,000 ventilators in the U.S., and we are likely going to need much more. As the virus spreads, 25% of cases will require hospitalization, and about 44% of those cases will require ventilators. If projections are correct, this means 96 million cases, of which 4.8 million will require hospitalization and 1.9 million will require intensive care units. Scary math.

One of the most important solutions we need to address are tests for the virus itself. There are three primary reasons why we have a shortage of tests:

- The FDA established an “Emergency Use Authorization” (EUA) policy, which complicated the ability of physicians to get access to tests. Red tape and the slow reaction time of the FDA to authorize testing has been a major hindrance.

- Testing has been held up an inability to get access to virus samples. To conduct testing requires access to samples and specimens of the coronavirus reagent. The coronavirus originated in China, and as several microbiologists told me, the Chinese government does not allow specimens to be shipped outside its borders.

- There is a lack of equipment needed to conduct the tests. The test requires special instruments that extract and then amplify the RNA that makes up the virus. However, labs across the country—like those at many county hospitals—don’t have the tools to do this. Even though some hospitals actually have the new, functional CDC tests, the extraction machines and reagents that are used to perform them are in short supply.

So what can be done? We need leaders to think about how to drive increased standards and line of sight and access to equipment, specimens, and procedures to address these shortfalls. A special task force should be working to streamline access to tests and equipment across the country, establishing special testing centers.

Read the long-form version of this story here.

- Categories:

- Series: