The Pros and Cons of Wealth Taxes

Vice President Kamala Harris’s proposal could shrink the federal deficit—or send the wealthy overseas.

One of Vice President Kamala Harris’s centerpiece policy proposals is a wealth tax—a 25-percent minimum tax on unrealized gains for taxpayers whose net wealth exceeds $100 million. If enacted, the tax could bring in more than half a billion dollars of tax revenue over the next decade.

A tax on individual wealth is one path toward reducing the federal deficit, which sits at an all-time high of more than $35 trillion. But it is not without its challenges. Let’s explore why taxing wealth (rather than income) is harder than it may seem.

U.S. Taxes: Income, Not Wealth

But first, some background on the federal tax system. The federal government taxes an individual’s income at rates ranging from 10 percent for the lowest-earning taxpayers to 37 percent for the highest earners.

The key word there is “income”—the federal government collects taxes on what people earn, not what they own. NBA superstar Lebron James has a 2024-2025 NBA season salary of $47.61 million. He’ll pay federal income taxes at a rate of 37% on almost all of that income.

Compare that to Mark Zuckerberg. As the CEO of Meta (the parent company of Facebook), he is paid a salary of $1. While additional compensation in company stock raises his annual earnings to around $24 million, the vast majority of his $204 billion net worth comes from the increase in value of his holdings in Meta rather than his ordinary income.

A large amount of Zuckerberg’s $204 billion has gone untaxed. That’s because most of his wealth comes from the increasing value of his assets, which won’t be taxed until he realizes a gain from them (i.e., the securities are sold).

An analogous situation is the gain taxpayers face when they purchase a home that increases in value. They don’t owe taxes on yearly increases in the home’s value. Instead, they pay taxes on the gain when they sell the house.

The U.S. currently designs its tax system under a “wherewithal to pay” policy principle, meaning that taxes usually correspond to an increase in the taxpayer’s liquid assets—the cash available to pay tax. A wealth tax would require taxpayers to pay at regular intervals on the appreciation of their assets, regardless of whether they have the cash or liquid assets to pay.

A Reality Check for Unrealized Gains

Harris is proposing an expanded calculation of “total income” that would include unrealized gains in wealth. Under her plan, high-wealth taxpayers would likely pay taxes on their capital gains each year as their assets appreciate in value. Rather than waiting until their shares are ultimately sold, these “prepayments” would then offset some of the gains on an eventual sale to yield the net taxes owed. Importantly, the proposal is only for taxpayers with wealth in excess of $100 million. Only the ultra-wealthy would bear this additional tax and compliance burden.

Imposing additional tax burdens on the ultra-wealthy is often a popular place to look to address federal fiscal health. Many support it because, in theory, it just accelerates payment of ultra-wealthy payers’ tax burdens.

Consider Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones, who bought the team in 1989 for $140 million. Today, the team is worth $11 billion. Jones’s investment has appreciated by $10.8 billion. If he sold the team today, he’d pay a 20-percent capital gains tax. Harris’s proposal would tax the unrealized gain now and annually as the team’s value rises.

Net worth threshold for Kamala Harris’s proposed wealth tax

Another benefit of this proposal is that it only applies to about 2,600 people. While the average taxpayer may balk at a 25-percent tax increase, virtually none of them would be affected by it. The burdens would fall just on the ultra-wealthy.

The proposal would also ensure taxpayers actually pay taxes on their investments. There’s a common scheme used by wealthy taxpayers called “Buy, Borrow, & Die”. Here’s how it works: A person invests money in an asset (like a sports team) and borrows against that investment to meet ongoing cash needs. The interest they pay on that debt is tax-deductible, reducing their tax burden. They hold the investment until they die, when the asset’s tax basis—its value for tax purposes—may get stepped up. Their descendants inherit the asset at its current value, with little or no taxable event.

Not all wealthy taxpayers benefit from this strategy. Estate taxes—or “death taxes”— may reduce its value. And Harris’s proposed wealth tax wouldn’t entirely close the loophole it exploits. But it would be considerably less profitable for wealthy taxpayers.

More Money for the Treasury. More Problems for Payers?

The clearest concern with this proposal is the administrative burden it would put on taxpayers and the taxing authority. Most notably, it’s unclear how taxpayers would assess the value of their assets at year-end. A taxpayer who primarily owns stock could simply look at the value of their holdings on Dec. 31 and assign their wealth a value.

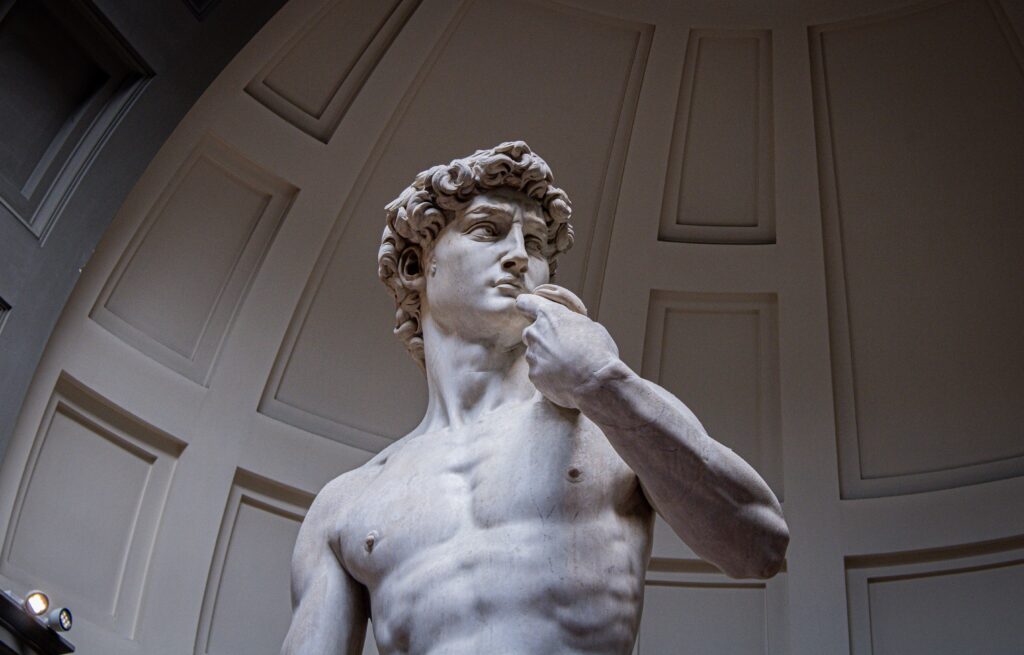

But what about sports team owners? Sure, there are estimates of what each franchise is worth. But they’re just estimates and may not be very rigorous. What if a taxpayer owns many priceless works of art? Paintings by Monet and sculptures by Michelangelo are often one-of-a-kind pieces and don’t have a liquid market.

It would be virtually impossible to determine the net worth of a taxpayer who holds such items. It would be even harder to determine the annual change in the value of those assets. Taxpayers would most likely have to pay for annual appraisals. Perhaps even more burdensome, the Internal Revenue Service would need to assess taxpayers’ net worth, as well as the value of their assets, and whether taxpayers’ reported values are reasonable.

Another concern with Harris’s proposal is that it violates two standards for a good tax policy. The first has to do with a person’s ability to pay a given tax. Even a very wealthy individual may not have the liquid assets to pay the tax on their changes in wealth.

The second standard it violates is related to economic efficiency. Tax laws shouldn’t force taxpayers to do things they wouldn’t otherwise do. Under Harris’s proposal, taxpayers who don’t have cash to pay taxes may have to borrow money or sell. That dampening of economic efficiency could have other economic effects. For example, the wealth tax could discourage risky investments, such as angel investing and entrepreneurship. In our capitalistic system, such investments are believed to help facilitate job growth and innovation, and a wealth tax could have the opposite effect.

A final concern with this proposal would be capital flight. Very few countries levy wealth taxes, and those that do tend to impose much smaller ones than those proposed by Vice President Harris. If wealthy taxpayers faced this burden, they may reconsider their U.S. residence and citizenship. If a wealth tax would cost somebody like Elon Musk billions of dollars, would he simply maximize his economic value and move to a place like the United Kingdom, where his tax burden would be in the tens of millions? The flight of capital out of the U.S. coulhave immediate and long-term negative effects on U.S. tax revenues. Norway, a country with a wealth tax, experienced significant capital flight following its implementation.

Congress and the Courts Have a Say

Over these last few weeks before the Nov. 5 presidential election, we’ll hear more about the candidates’ economic ideas and tax plans. Ultimately, any changes to the U.S. tax law are the responsibility of the U.S. Congress. Even with the support of Congress, any president who wants to make radical changes to tax law (not unlike this proposal) would face legal battles over the constitutionality of taxing something other than income. It’s also noteworthy that there are other, more straightforward ways to increase tax collection from the wealthy, such as a progressive tax on consumption. Regardless of the future prospects for a wealth tax, Harris’s proposal has generated significant discussion about whether wealth should be subject to taxation.

Nathan Goldman and Christina Lewellen are associate professors of accounting in the Poole College of Management.

- Categories: