How To Craft an Optimal Unilateral Carbon Policy

Climate change is a global problem that gets addressed by individual countries. Poole College scholars recently shared research on the optimal policy for a fragmented world.

The Devils and Wolves seminar series brings high-quality research in international economics to the Triangle.

In this column, Poole College’s Andrew Greenland, assistant professor of economics, and Luca David Opromolla, Owens Distinguished Professor of International Economics, share research presented at the April 12 seminar.

Controlling the emission of greenhouse gasses is a global issue that could be addressed more effectively with a globally harmonized carbon price. But planned and active measures to deal with it vary considerably across countries.

The problem with this each-country-for-itself approach to climate policies is that it can result in leakage: extraction of fossil fuels, production that relies on fossil fuels, and consumption of energy-intensive goods may shift to regions of the world where climate policies are less stringent. Is there hope for a coalition of countries to design an effective unilateral climate policy?

In an upcoming study, Samuel Kortum, James Burrows Moffatt professor of economics and management and director of the Cowles Foundation at Yale University, and David A. Weisbach, the Walter J. Blum professor of law at the University of Chicago Law School, describe the optimal carbon policy for individual countries and coalitions of countries to adopt in the absence of global cooperation. It’s a combination of supply-side and demand-side taxes, as well as export subsidies for greener goods.

International trade is the key to the effectiveness of such a unilateral policy. While a single country can’t control extraction, production and consumption activities outside its borders, it can indirectly affect those overseas activities by influencing the prices for traded energy and goods.

Kortum and Weisbach’s optimal policy relies on three measures:

- A domestic carbon tax on energy extraction at a rate that follows the global harm from greenhouse emissions

- Border adjustments in the form of a tax on imported energy (and energy embedded in trade goods) and a rebate of taxes on exported energy—both at a lower rate than the extraction tax rate

- Subsidies that encourage low-carbon exports

The optimal policy shares some common elements with the European Union Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and every carbon tax bill currently in Congress. But Kortum and Weisbach argue that the combination of supply-side and demand-side measures would yield superior outcomes to the EU and congressional measures.

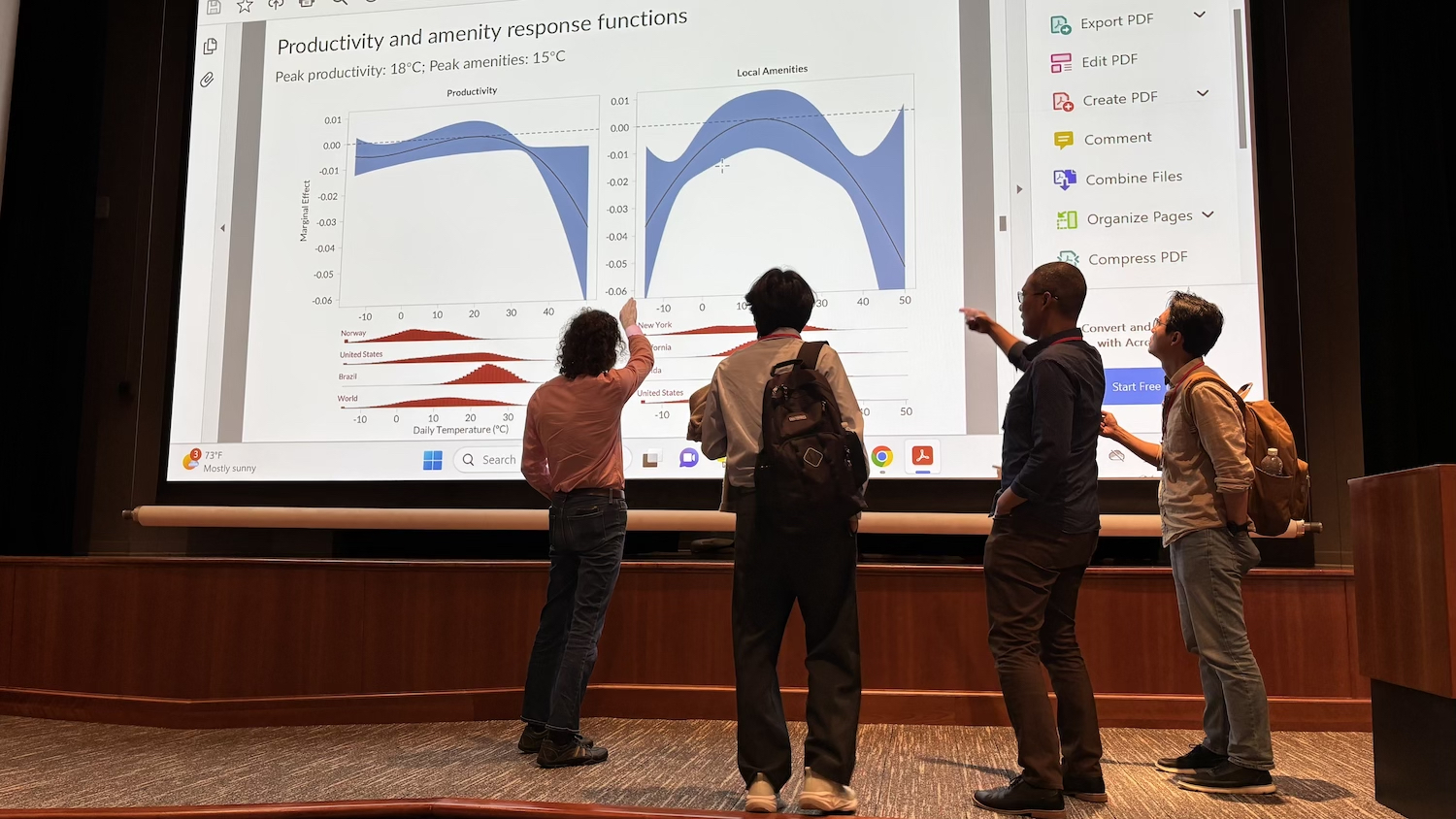

How would the optimal unilateral policy play out? It would be ideal, at a global level, to tax carbon at a rate equal to the global social cost. But a unilateral policy can’t do that. What it can do is affect extraction and consumption patterns in the rest of the world based on how those activities react to the global energy price.

Consider a scenario where a coalition of countries adopts the optimal unilateral policy. Fossil fuel extraction activities in countries outside the coalition are very reactive to the price of energy. If the coalition aims at reducing these extraction activities, it should depress the price that foreign energy extractors receive.

If, instead, foreign energy demand (both for the energy itself and for trade goods with high embedded energy) is a more effective lever, then a higher global price of energy would do the trick.