Bridging the Rural-Urban Divide in Healthcare

Research shared by Poole scholars suggests that subsidizing patient travel may be a cost-effective approach.

The quality and availability of medical services differs greatly between urban and rural areas.

New analysis from Jonathan Dingel, associate professor of economics at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, and his cauthors explores what can be done to ameliorate these differences—and what models of international trade have to do with potential solutions.

Rural Americans tend to have worse health outcomes than their urban counterparts. This is in part driven by the fact that urban medical centers provide a plethora of treatments unavailable in smaller rural centers. For a long time, people have suggested an obvious, but perhaps incorrect, solution: subsidize medical care in rural areas to improve patient access. Yet, this intuitive suggestion, Dingel and his co-authors find, may be missing a very important feature of medical treatment: economies of scale.

When doctors set up facilities to care for patients, they must cover a lot of costs that are unrelated to the immediate care of every patient. Yes, every patient needs to step on a scale every visit, but not every patient needs a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. So it makes a lot of sense for your primary care provider to have a scale in their office, but very little sense for her to have an MRI machine sitting in the back. If she did have one, she’d have to charge an exorbitant amount per scan to spread the costs of the machine across the few patients a year who might need one.

Hospitals, by contrast, see so many patients that the cost per scan is substantially lower. Some types of medical treatment, like MRIs, exhibit economies of scale—the per-patient cost of offering them is far lower in a high-volume establishment like a hospital than a low-volume one like a general practitioner’s office. While this idea is prevalent in the study of international trade, Professor Dingel’s insight was to apply it to the trade in medical services between sparsely populated rural areas and more densely populated urban areas.

The same is true of rare conditions that demand specialized equipment and care. As a rule, these conditions also require more training for medical providers, and treatment for them is most likely available only in large, dense cities. This is why people seem so willing to travel great distances for treatment of very rare diseases.

In that light, it’s obvious that big cities can offer the scale to support specialized medical services. That also suggests why subsidizing medical care or moving doctors to rural areas is unlikely to be the most cost-effective fix. Yes, we could make it so that every rural hospital has an MRI machine or top surgical unit, but the small scale of these operations would ensure a high per-patient cost per-patient.

Even spreading the cost across all patients in these rural areas would be less effective than a simpler policy centered on subsidizing the cost for medical travel to these major urban centers. Doing so would move the relatively few patients who need care for any particular ailment to the centers where it’s already being done at a higher quality in a more cost-effective manner. Instead of driving up costs locally, this might even drive down the cost or increase the quality in more urban centers.

Dingel and the others don’t study Just how to craft such a policy, but their research does suggest some new avenues for policymakers to explore if they really want to get better healthcare to rural patients in a cost-effective way.

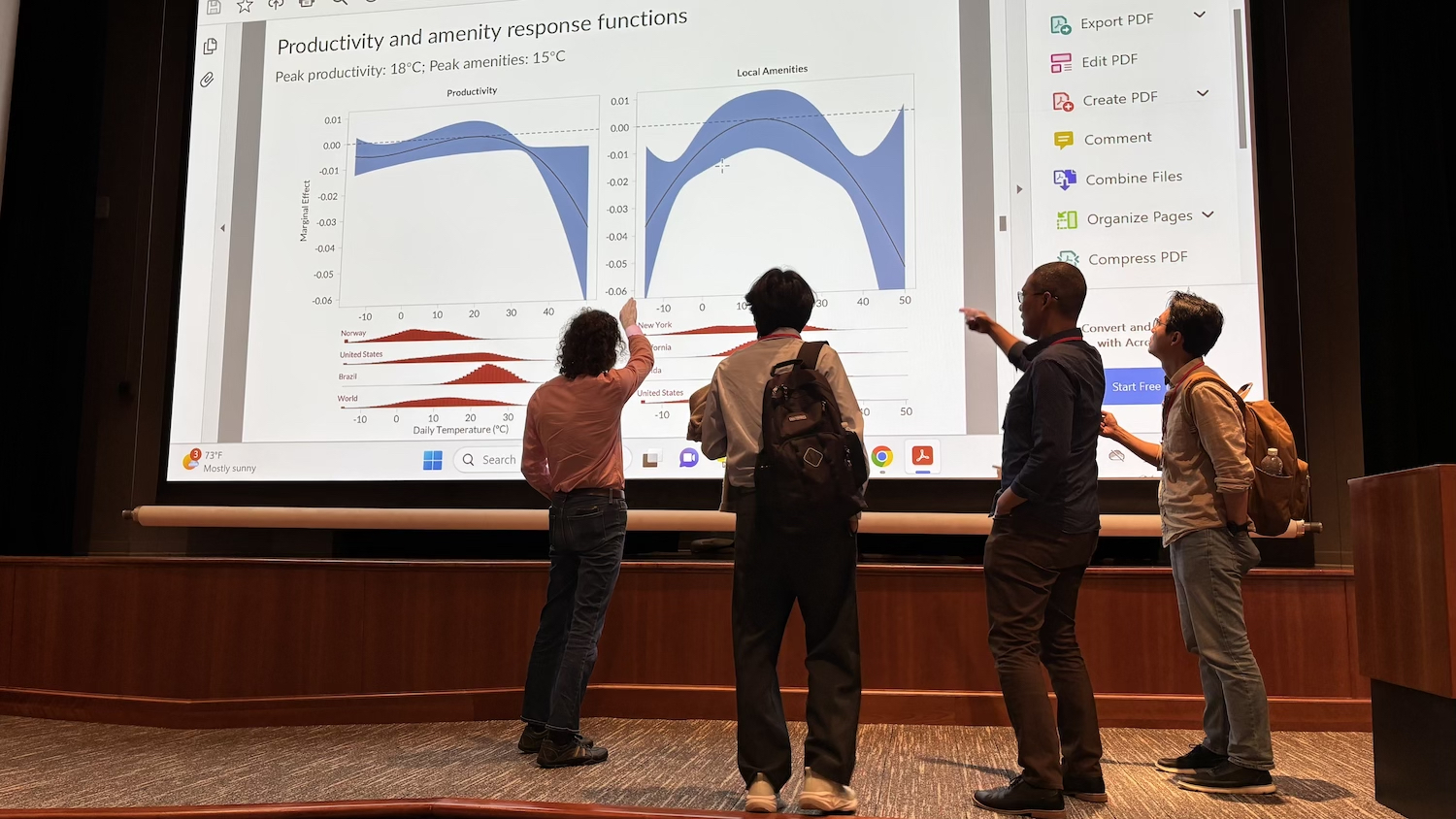

This article is based on a recent talk at the Devils and Wolves seminar series. Jointly sponsored by NC State, Duke and the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, the series brings high-quality research in international economics to the Triangle. At each session, Opromolla and Greenland discuss research on relevant topics.

Luca David Opromolla is the Owens Distinguished Professor of International Economics in the Poole College of Management and the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. He studies international trade, industrial organization and labor dynamics.

Andrew Greenland is an assistant professor of economics in the Poole College of Management and an assistant professor of economics in the Department of Agriculture and Resource Economics in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. He studies U.S. trade policy and the effects of globalization on the U.S. throughout its history.

- Categories: