Why Some U.S. Downtowns Are Stuck in a Moment (They Can’t Get Out Of)

Poole College's Andrew Greenland and Luca David Opromolla share new research presented at the Devils and Wolves International Economics Seminar Series.

The Devils and Wolves International Economics Seminar Series brings world-class research in international economics to the Triangle. These Poole Thought Leadership columns build on the research presented at the seminars to help entrepreneurs, policymakers and journalists better understand key current trends in the global economy.

In this column, Poole College’s Andrew Greenland, assistant professor of economics, and Luca David Opromolla, Owens Distinguished Professor of International Economics, share research presented at the Feb. 2 seminar.

The information technology revolution has dramatically lowered the cost of processing and transmitting information across long distances. An increase in remote work is one likely outcome of that freer, faster flow of information. But, through 2019, ways of working had only changed marginally.

Then, the COVID-19 pandemic changed everything. White-collar work moved to people’s homes, vacating office buildings and depressing the businesses around them.

Central business districts in smaller U.S. cities have returned to pre-pandemic activity levels faster, while larger ones remain empty.

City planners, politicians, economists, and environmental organizations are increasingly discussing how city organization affects growth, pollution, and society. Proponents of the 15-minute city — where people can access jobs, housing, shopping, health and education facilities within a short walk, bike ride, or public transit trip from one’s home — emphasize the potential substantial cut in emissions as a result of lower commuting. But economic activity sometimes requires a larger scale, and overly strict regulations can collide with market mechanisms and defy the purpose.

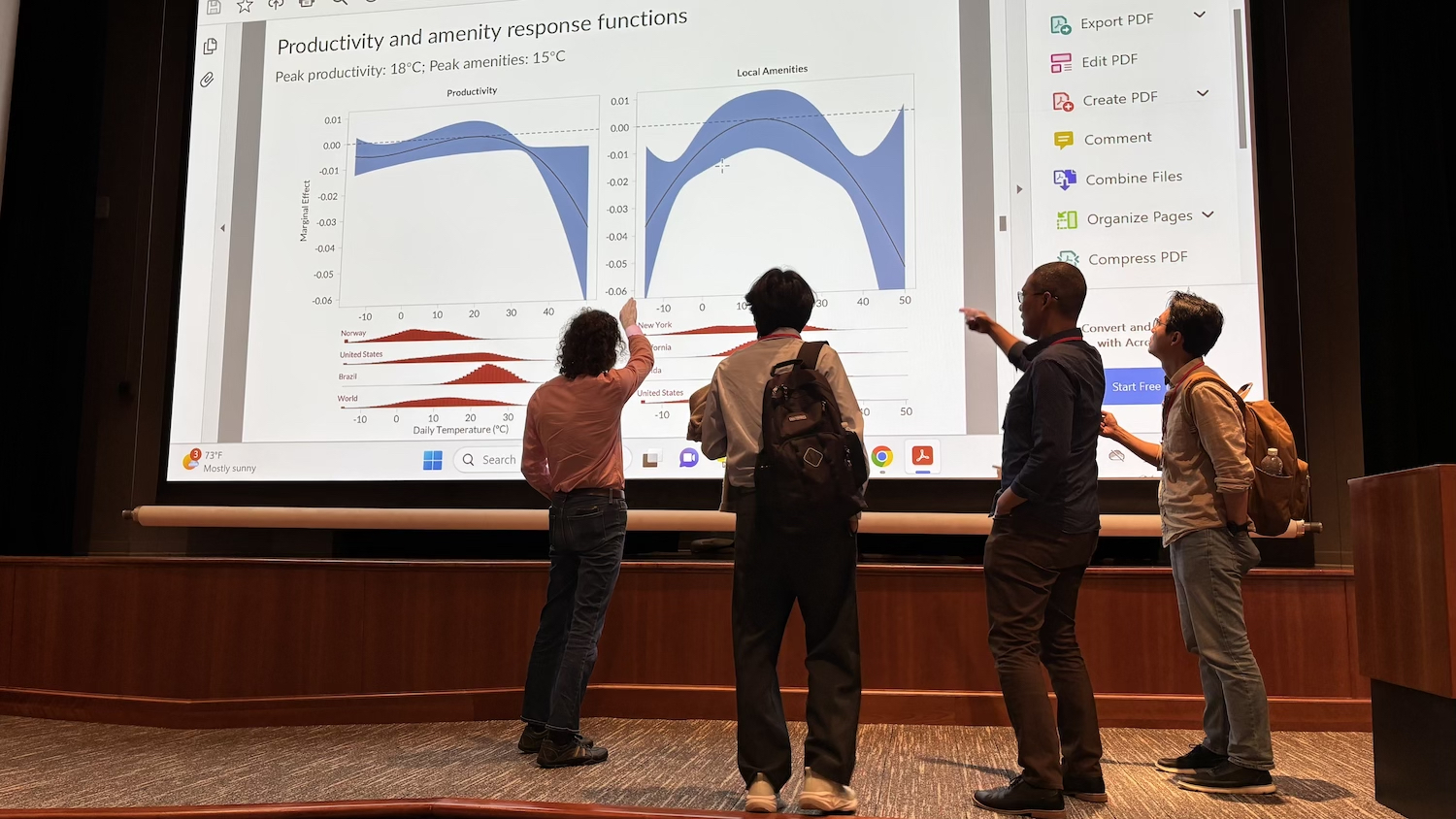

In a Feb. 2 Devils and Wolves seminar, Ferdinando Monte, associate professor of economics at Georgetown University, presented new research that explores the economic forces that drive people to work from home rather than commute to central business districts.

Monte attributes the uneven return to office work to two key components.

First, workers benefit from being in the presence of other productive workers — that’s a significant reason employers encourage office work in the first place. People may learn about cutting-edge solutions from colleagues, or they might be the ones providing the help.

Most of the time, firms will pay workers more for that extra productivity. But some of the benefits of that extra output (productivity spillovers) accrue to others. That means workers’ wages don’t reflect the true value they create in office settings.

Meanwhile, by bearing the cost of commuting to the office for work, workers do have to internalize the cost of that extra productivity.

When colleagues continue to show up at work, each individual worker has the same incentives. As a result, you get cities with vibrant business districts and downtown areas. People benefit from this uncoordinated equilibrium — I go into the office because you go into the office and vice-versa — and as a consequence we all derive enough benefit to offset the cost of commuting.

While this seems straightforward, the author’s analysis reveals that, in many types of cities, this is the only possible outcome. The costs of commuting are so small compared to the benefits of being among more productive workers that nearly everyone will choose to work in person.

In other, often substantially larger cities, however, the costs of commuting are large and the value created by high-productivity individuals accrues to others (rather than boosting their own wage).

In that circumstance, there’s just enough incentive to come into the office, but only because everyone else already does. If everyone else decides to stay home, the incentives will shift in ways that could become permanent. In these types of cities, where both a work-from-home equilibrium and a work-in-person equilibrium can occur, the pandemic has had particularly devastating effects on the downtown.

When the pandemic struck, a tremendous share of the population was thrust into a work-from-home environment. For smaller cities, the draw of the productivity gains outpaced the cost of short commutes, and workers eventually returned to the office.

But for many of the larger cities, the weak draw of minor productivity enhancement wasn’t enough to offset the substantial costs of getting downtown. In other words, the pandemic served as a coordination device that shifted these larger cities into the new work-from-home-equilibrium.

This hasn’t just shifted commuting behaviors. It’s also had substantial implications for housing prices. Rent in urban centers plummeted substantially across nearly all cities at the height of the pandemic, but as economic activity rebounded, housing prices and rent didn’t automatically follow suit.

Many of the locations where work-from-home became the new norm saw downtown housing prices rebound at a much slower rate and to a much lesser extent than the cities which experienced a full return to office work equilibrium.

By contrast, housing prices have risen more sharply in the suburbs, where remote work has become the norm.