Why Tradable Services Cluster in City Centers

Poole scholars share research on what brings firms in financial, consulting, legal and other services to urban hubs.

The United States is an important producer and exporter of services, and this type of production tends to be concentrated in major metropolitan areas. Why these high-paying, tradable services jobs show up in some locations and not others is an important question when evaluating the gains from trade and globalization.

In their paper, Prime Locations, a research team including Kristian Behrens, professor of economics at the Université du Québec à Montréal, recently analyzed data on the location of all establishments in three major U.S. cities—New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago—to identify the “prime locations” for financial, consulting, law and other tradable services. These locations, they found, account for more than 20 percent of a city’s employment, but only account for roughly 0.5 percent of its land.

Some cities, Chicago among them, only have one prime location—its city center, essentially. New York has two, while Los Angeles has multiple. Yet, no matter how many prime locations each city has, these city centers have a disproportionately large share of employment in tradable services. Employment in these fields is known to benefit from agglomeration economies—the idea that firms of a certain type are more productive when they are co-located with other similar firms. This may occur, for example, due to cross-pollination of ideas or thick labor markets for highly technical workers that allows firms to find an ideally matched candidate for a particular position.

With this insight in mind, Behrens and his co-authors document the prevalence of these prime locations in the biggest cities across the planet and seek some explanation for why they popped up where they did. Internationally, they find that this service sector employment is highly concentrated in cities and, as in the U.S., those cities differ only modestly in how many prime locations they feature.

The largest share of cities feature a monocentric structure, like Chicago, where one central business district dominates and smaller establishments and housing surround the center. However, a large share of cities feature two centers and some (like Los Angeles) feature even more.

What can explain these differences and why does it matter?

The authors show that, historically, early investment in transportation infrastructure like rail was a key predictor of having only one center. These investments made it much less costly for workers to get from the suburban outer ring into the city center for work.

Once a city started down this path, the monocentric structure became self-reenforcing. The transportation infrastructure meant that workers could easily access the city center without tying up valuable land that could be used for production. Because this land was earmarked for production, it provided the benefits associated with agglomeration economies which made it even more beneficial to locate further production nearby and made these cities very dense economically As a result these early adopters and mono-centric cities tend to have even more tradable service employment than their equally large counterparts with two (or more) city centers.

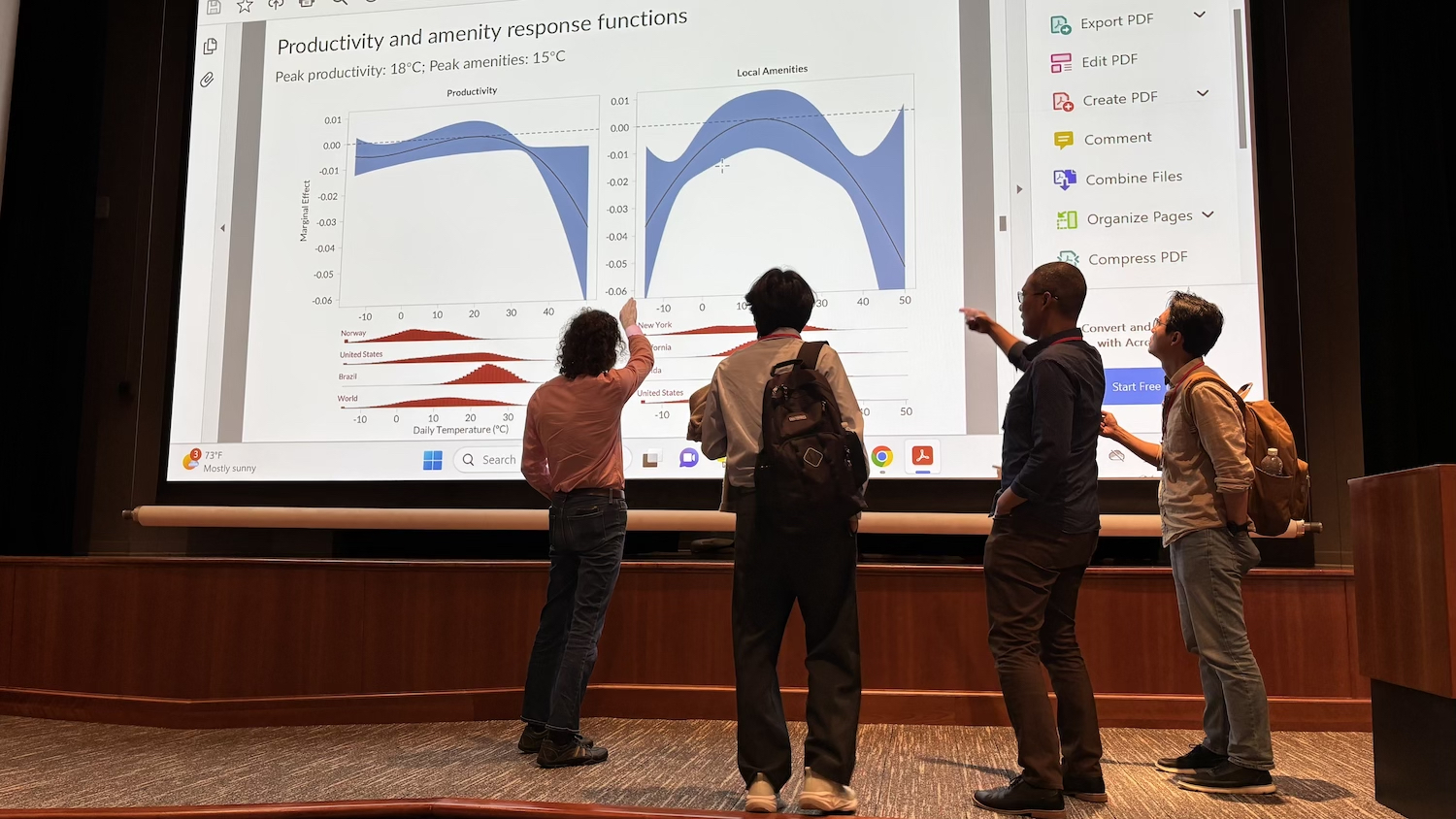

This article is based on a recent talk at the Devils and Wolves seminar series. Jointly sponsored by NC State, Duke and the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, the series brings high-quality research in international economics to the Triangle. At each session, Opromolla and Greenland discuss research on relevant topics.

Andrew Greenland is an assistant professor of economics in the Poole College of Management and an assistant professor of economics in the Department of Agriculture and Resource Economics in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. He studies U.S. trade policy and the effects of globalization on the U.S. throughout its history.

Luca David Opromolla is the Owens Distinguished Professor of International Economics in the Poole College of Management and the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. He studies international trade, industrial organization and labor dynamics.

- Categories: